Autocracy is Already Killing our Minds, but Incentives Are Aligned to Fight Back

The Rule of Law Provides Stability and Predictability that Allows Us to Flourish

One of the many dangers of autocracy is that it saps energy and creativity. College professors are currently not talking about their research because they are too busy worrying and discussing the extortionary attacks on higher education coming from the Trump administration. International students and their allies are not focused on their studies because they are worried about being picked off the streets by government agents. You may be unfocused on your work and family because of the catering of the stock market.

You may be familiar with the last of these problems, but if you are not a college campus, let me assure you that the first two of these phenomena are real: people at universities are getting very little done because they are too busy worrying about Trump and his ongoing or potential attacks on universities and their students. This kind of damage doesn’t show up immediately in our ledgers but is immensely costly, nevertheless. Ever hear those stories about the massive downturn in productivity because everyone is watching the NCAA Tournament on streaming services? It’s like that, but this time, it is because of fear. No, really, people on college campuses are afraid and uncertain.

This is one of the many consequences of the weakening of the rule of law: it takes away the certainty we have. When the rule and stability of law provides reassurance, freedom of thought flourishes. When the rule of law goes away or is uncertain, freedom of thought is curtailed, too. Under the rule of law, when Congress allocates money for scientific funding, you can be sure it will be there next year, and you can plan your research. But that is no more. Most of us will not be subject to the arbitrary arrest that Trump has extended to our most vulnerable students, but our concern about it saps our energy.

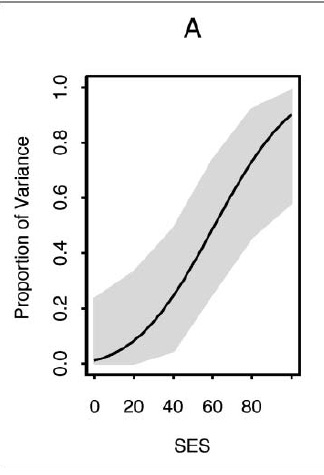

In a sense, such uncertainty, the guessing about what comes next, hurts our minds—it dumbs us down. A famous demonstration of this comes from a study of how much of the variance in IQ explained by the environment varies across socio-economic status.[1] The study asked how much of IQ is genetic and how much is caused by the environment in which a person lives[2]. In genetics, sometimes to the surprise of people not familiar with the literature, heritability, that is the amount of a trait that is determined by genetics, varies across contexts. So, in one setting, something like IQ might be highly determined by genetics, but not in another setting. This makes sense when you think about it: imagine an extreme circumstance where nobody received any schooling whatsoever. In this case, almost all variation in IQ would be explained by genetics because there would be no variation in the environment. The study about IQ and socio-economic status showed that among those with low socio-economic status, variation in the environment can greatly influence IQ. You can see how this can be a function of uncertainty: the worry about food or violence, or other such matters that come with poverty, might make it hard for some people to express their intelligence and flourish. In contrast, at the highest ends of socio-economic status, when the environment is often stable, the environment has almost no effect on IQ, and rather, it seems to all be affected almost entirely by genetics. There is no variation in hunger or violence or anything else, and so all that is left is one’s natural intelligence.

This contrast—the destabilizing effect of poverty and the leveling effect of affluence—is reflected in my experience, moving from teaching in a poverty-stricken urban neighborhood when I taught high school in Englewood on the Southside of Chicago to teaching at the richest university in the world. The natural intelligence of students in Englewood showed brilliantly when they were well-fed and not worried about what would happen next. When anxiety entered the neighborhood, when fear of crime or something else grabbed their attention, they were distracted, and it was hard for them to learn. The sociologist Patrick Sharkey showed this when he demonstrated that for high school students in Chicago, academic performance dropped when fatal shootings occurred in the neighborhood in close proximity to the time they took the test.[3] Contrast this with Harvard at normal times, where students, more or less, never worry about what will happen next and, if they choose, their genius shines through.

In a certain respect, authoritarianism takes this impoverishing effect and extends it to us all. Harvard professors will be okay, of course. But there is a loss when scientists can’t concentrate on what they are supposed to concentrate on. Take this and extend it to other people: the immigrants, lawyers, and reporters targeted by Trump, and you can start to understand the creative productivity a society can suffer under authoritarianism.

In addition to the loss from the uncertainty created by authoritarianism arbitrariness, authoritarianism also hurts our expression because of fear. It makes us think about what we can and cannot say. It lays a chill over our statements. Students are worried that their social media will be used to test their immigration status. Faculty worried that their scholarship may be turned against them. Creativity and expression die when you have to stop and ask if there might be damage from what you are about to print. Solzhenitsyn, who had been a writer in the USSR and spent years in the Gulag, wrote about how the scientists spent their energy trying to avoid the wrath of the regime. There is a reason that we thought of the autocratic countries behind the Iron Curtain as so gray and bleak—it’s because censorship can kill the creative spirit. Authoritarianism has the potential the sucking of our national soul.

Nearly every conversation I’ve had with other professors—and students—in the last several weeks has been about Trump’s anticipated extortion of Harvard and what Harvard should do in response. Trump is demanding that Harvard relinquish control of its governance, much like he did to Columbia, or lose billions of dollars in federal funding. These demands are unlawful, as my colleagues in the law school have pointed out, and are formed on the pretext of Harvard not doing enough to combat antisemitism on campus. At some point, I’ll write more about the wildly overblown claims of antisemitism on America’s college campuses but, for now, I think it should be plainly obvious that the Trump administration, home of people who think Nazi salutes are funny, does not care about antisemitism. Harvard has a choice about whether to resist these demands and possibly face a costly showdown with the federal government or capitulate like Columbia and lose its academic freedom.

This situation, of course, is felt by many institutions across the country, both the other universities attacked by Trump and also the other segments of civil society. Authoritarians are like bullies, menacing the schoolyard and casting a shadow over the playground of our civil society. Some other elite institutions, like white-shoe law firms and large news agencies, have capitulated, casting a further shadow over society.

Many of us fear that Harvard is already capitulating too: they fired the directors of Center for Middle Eastern Studies, ended public health partnerships with universities in the occupied West Bank, and suspended programs focused around Middle Eastern Peace in the Divinity School. They have already restricted speech. Presumably, all these actions are not a cosmic coincidence, but rather attempts to mollify Trump and his allies.

The loss of concentration comes as we look at the uncertainty of not knowing what the university will ultimately do in response to these attacks and not knowing the consequences if we fight back or if they capitulate. If they fight back, will Trump try to come down harder in his vindictive way? If we capitulate, we will be on edge, always wondering if he will come back demanding more. And anxiety also comes from knowing that what Harvard does will leave a mark on it: we anticipate the shame of living with this capitulation. This is authoritarianism sucking our soul, leaving a shame of complicity on Harvard that many are already feeling. We go to work every day and teach, talk to students, carry on our research, knowing in the background that our institution is caving on the values it claims to hold dear.

So, where does that leave us on what to do? Should Harvard push back? My coauthor, Steve Levitsky, and I have laid out the case that Harvard must resist the actions of the Trump administration in two op eds, and we circulated a letter saying so that over 800 faculty have signed. Doing so will, at least, eliminate some uncertainty. And it will eliminate the possibility of having to live with the shame of complicity.

I also think fighting back is the right strategy both if Harvard simply wants to protect its money and, more importantly, if it wants to do the right thing. This is to say that both strategic and ethical incentives align. In many cases in the public sphere, including in politics, we face tough decisions about doing what is right for our own narrow interest and doing what will allow us to sleep well at night. The most classic example of this is the single-shot prisoner’s dilemma where two prisoners are given the option of ratting on their fellow inmate and receiving a lighter sentence. The short-term strategic incentive is for the prisoner to rat on his fellow prisoner and reduce his punishment, even if it is the unethical thing to do. This sort of unalignment between strategy and ethics also happens with, say, a whistleblower, putting his own future at risk to point out when somebody is doing something wrong. The ethical thing is to blow the whistle, but it might not be individually strategic.

But in some cases, the strategic and ethical incentives do align: for example, if a Prisoner’s Dilemma is played over and over again, the prisoners are better off cooperating with each other in the long run, both treating each other well and defending each other’s interests. For universities, too, because their showdown with Trump will not only happen once, the strategic imperative is obvious: Trump operates as a mob boss, and we all know that protection money is not paid just once. Trump will keep coming back to bend universities to his will because the point is about power, not policy. The strategic incentive is not to give in: it just can’t possibly be in the long-term health of the university to do so. The moral incentive is also obvious because these leaders will have to ask themselves what decision will help them to sleep well at night: one that protects the university in the short term and sells its soul or one that aligns its long-term moral and strategic incentives.

So, what is holding the leaders of elite institutions, like Harvard, back? Why aren’t they doing the right thing if the incentives are so aligned? One answer is fear or cowardice or, perhaps, more generously, risk aversion: not wanting to cause an even bigger problem for the university. Many colleagues have suggested to me that it might be because the leadership at many universities also are not entirely opposed to what the Trump administration wants to do. Many college leadership boards are not made of professors, but rather rich people who don’t care that much about academic freedom and might not care that much about losing the Center for Middle Eastern Studies or free speech for college sophomores. That is a sad situation, but it seems very plausible to me.

I think it’s also the case that many elite institutions are hamstrung by their eliteness. That they feel like the institution itself becomes all that is worth protecting—that Harvard, because it is Harvard, has to be protected. They don’t want to be responsible for causing damage to an institution that is older than the country itself.

Other institutions are less constrained by this self-regard. At the massive Hands Off protests in Boston last Saturday, many institutions, other than universities, were fighting back against Trump in a way that gave me much hope for American civil society. Not only did the feeling of fighting back, rather than sitting on our hands and worrying, feel like it cast off the oppressive shadow of the Trump administration, but it showed how many institutions are not constrained by a paralyzing self-importance of the type that seems to afflict Harvard and other elite institutions. Organizations like the AFL-CIO and the teachers’ unions sponsored these protests and proudly stood up to Trump. To be sure, this is easier for them because they are political in nature. But taking a step back from the Hands Off protest itself, we see that these organizations also have some freedom to do the right thing because they are interested, not in protecting the organization qua the organization, but in standing up for what they were formed to stand up for. Their members and leaders certainly will be able to sleep well at night knowing that they did the right thing. I hope those of us at places like Harvard will, too.

[1] Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D'Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychol Sci. 2003 Nov;14(6):623-8. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. PMID: 14629696.

[2] This was a twin study, for those who care.

[3] Patrick T. Sharkey, Nicole Tirado-Strayer, Andrew V. Papachristos, and C. Cybele Raver: The Effect of Local Violence on Children’s Attention and Impulse Control. American Journal of Public Health 102, 2287_2293, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300789